Privacy-preserving p2p economic spam protection in Waku v2

This post is going to give you an overview of how spam protection can be achieved in Waku Relay through rate-limiting nullifiers. We will cover a summary of spam-protection methods in centralized and p2p systems, and the solution overview and details of the economic spam-protection method. The open issues and future steps are discussed in the end.

Introduction

This post is going to give you an overview of how spam protection can be achieved in Waku Relay protocol1 through Rate-Limiting Nullifiers2 3 or RLN for short.

Let me give a little background about Waku(v2)4. Waku is a privacy-preserving peer-to-peer (p2p) messaging protocol for resource-restricted devices. Being p2p means that Waku relies on No central server. Instead, peers collaboratively deliver messages in the network. Waku uses GossipSub5 as the underlying routing protocol (as of the writeup of this post). At a high level, GossipSub is based on publisher-subscriber architecture. That is, peers, congregate around topics they are interested in and can send messages to topics. Each message gets delivered to all peers subscribed to the topic. In GossipSub, a peer has a constant number of direct connections/neighbors. In order to publish a message, the author forwards its message to a subset of neighbors. The neighbors proceed similarly till the message gets propagated in the network of the subscribed peers. The message publishing and routing procedures are part of the Waku Relay6 protocol.

What do we mean by spamming?

In centralized messaging systems, a spammer usually indicates an entity that uses the messaging system to send an unsolicited message (spam) to large numbers of recipients. However, in Waku with a p2p architecture, spam messages not only affect the recipients but also all the other peers involved in the routing process as they have to spend their computational power/bandwidth/storage capacity on processing spam messages. As such, we define a spammer as an entity that uses the messaging system to publish a large number of messages in a short amount of time. The messages issued in this way are called spam. In this definition, we disregard the intention of the spammer as well as the content of the message and the number of recipients.

Possible Solutions

Has the spamming issue been addressed before? Of course yes! Here is an overview of the spam protection techniques with their trade-offs and use-cases. In this overview, we distinguish between protection techniques that are targeted for centralized messaging systems and those for p2p architectures.

Centralized Messaging Systems

In traditional centralized messaging systems, spam usually signifies unsolicited messages sent in bulk or messages with malicious content like malware. Protection mechanisms include

- authentication through some piece of personally identifiable information e.g., phone number

- checksum-based filtering to protect against messages sent in bulk

- challenge-response systems

- content filtering on the server or via a proxy application

These methods exploit the fact that the messaging system is centralized and a global view of the users' activities is available based on which spamming patterns can be extracted and defeated accordingly. Moreover, users are associated with an identifier e.g., a username which enables the server to profile each user e.g., to detect suspicious behavior like spamming. Such profiling possibility is against the user's anonymity and privacy.

Among the techniques enumerated above, authentication through phone numbers is a some-what economic-incentive measure as providing multiple valid phone numbers will be expensive for the attacker. Notice that while using an expensive authentication method can reduce the number of accounts owned by a single spammer, cannot address the spam issue entirely. This is because the spammer can still send bulk messages through one single account. For this approach to be effective, a centralized mediator is essential. That is why such a solution would not fit the p2p environments where no centralized control exists.

P2P Systems

What about spam prevention in p2p messaging platforms? There are two techniques, namely Proof of Work7 deployed by Whisper8 and Peer scoring9 method (namely reputation-based approach) adopted by LibP2P. However, each of these solutions has its own shortcomings for real-life use-cases as explained below.

Proof of work

The idea behind the Proof Of Work i.e., POW7 is to make messaging a computationally costly operation hence lowering the messaging rate of all the peers including the spammers. In specific, the message publisher has to solve a puzzle and the puzzle is to find a nonce such that the hash of the message concatenated with the nonce has at least z leading zeros. z is known as the difficulty of the puzzle. Since the hash function is one-way, peers have to brute-force to find a nonce. Hashing is a computationally-heavy operation so is the brute-force. While solving the puzzle is computationally expensive, it is comparatively cheap to verify the solution.

POW is also used as the underlying mining algorithm in Ethereum and Bitcoin blockchain. There, the goal is to contain the mining speed and allow the decentralized network to come to a consensus, or agree on things like account balances and the order of transactions.

While the use of POW makes perfect sense in Ethereum / Bitcoin blockchain, it shows practical issues in heterogeneous p2p messaging systems with resource-restricted peers. Some peers won't be able to carry the designated computation and will be effectively excluded. Such exclusion showed to be practically an issue in applications like Status, which used to rely on POW for spam-protection, to the extent that the difficulty level had to be set close to zero.

Peer Scoring

The peer scoring method9 that is utilized by libp2p is to limit the number of messages issued by a peer in connection to another peer. That is each peer monitors all the peers to which it is directly connected and adjusts their messaging quota i.e., to route or not route their messages depending on their past activities. For example, if a peer detects its neighbor is sending more than x messages per month, can drop its quota to z.x where z is less than one. The shortcoming of this solution is that scoring is based on peers' local observations and the concept of the score is defined in relation to one single peer. This leaves room for an attack where a spammer can make connections to k peers in the system and publishes k.(x-1) messages by exploiting all of its k connections. Another attack scenario is through botnets consisting of a large number of e.g., a million bots. The attacker rents a botnet and inserts each of them as a legitimate peer to the network and each can publish x-1 messages per month10.

Economic-Incentive Spam protection

Is this the end of our spam-protection journey? Shall we simply give up and leave spammers be? Certainly not! Waku RLN-Relay gives us a p2p spam-protection method which:

- suits p2p systems and does not rely on any central entity.

- is efficient i.e., with no unreasonable computational, storage, memory, and bandwidth requirement! as such, it fits the network of heterogeneous peers.

- respects users privacy unlike reputation-based and centralized methods.

- deploys economic-incentives to contain spammers' activity. Namely, there is a financial sacrifice for those who want to spam the system. How? follow along ...

We devise a general rule to save everyone's life and that is

No one can publish more than M messages per epoch without being financially charged!

We set M to 1 for now, but this can be any arbitrary value. You may be thinking "This is too restrictive! Only one per epoch?". Don't worry, we set the epoch to a reasonable value so that it does not slow down the communication of innocent users but will make the life of spammers harder! Epoch here can be every second, as defined by UTC date-time +-20s.

The remainder of this post is all about the story of how to enforce this limit on each user's messaging rate as well as how to impose the financial cost when the limit gets violated. This brings us to the Rate Limiting Nullifiers and how we integrate this technique into Waku v2 (in specific the Waku Relay protocol) to protect our valuable users against spammers.

Technical Terms

Zero-knowledge proof: Zero-knowledge proof (ZKP)11 allows a prover to show a verifier that they know something, without revealing what that something is. This means you can do the trust-minimized computation that is also privacy-preserving. As a basic example, instead of showing your ID when going to a bar you simply give them proof that you are over 18, without showing the doorman your id. In this write-up, by ZKP we essentially mean zkSNARK12 which is one of the many types of ZKPs.

Threshold Secret Sharing Scheme: (m,n) Threshold secret-sharing is a method by which you can split a secret value s into n pieces in a way that the secret s can be reconstructed by having m pieces (m <= n). The economic-incentive spam protection utilizes a (2,n) secret sharing realized by Shamir Secret Sharing Scheme13.

Overview: Economic-Incentive Spam protection through Rate Limiting Nullifiers

Context: We started the idea of economic-incentive spam protection more than a year ago and conducted a feasibility study to identify blockers and unknowns. The results are published in our prior post. Since then major progress has been made and the prior identified blockers that are listed below are now addressed. Kudos to Barry WhiteHat, Onur Kilic, Koh Wei Jie for all of their hard work, research, and development which made this progress possible.

- the proof time14 which was initially in the order of minutes ~10 mins and now is almost 0.5 seconds

- the prover key size15 which was initially ~110MB and now is ~3.9MB

- the lack of Shamir logic16 which is now implemented and part of the RLN repository3

- the concern regarding the potential multi-party computation for the trusted setup of zkSNARKs which got resolved17

- the lack of end-to-end integration that now we made it possible, have it implemented, and are going to present it in this post. New blockers are also sorted out during the e2e integration which we will discuss in the Feasibility and Open Issues section.

Now that you have more context, let's see how the final solution works. The fundamental point is to make it economically costly to send more than your share of messages and to do so in a privacy-preserving and e2e fashion. To do that we have the following components:

- 1- Group: We manage all the peers inside a large group (later we can split peers into smaller groups, but for now consider only one). The group management is done via a smart contract which is devised for this purpose and is deployed on the Ethereum blockchain.

- 2- Membership: To be able to send messages and in specific for the published messages to get routed by all the peers, publishing peers have to register to the group. Membership involves setting up public and private key pairs (think of it as the username and password). The private key remains at the user side but the public key becomes a part of the group information on the contract (publicly available) and everyone has access to it. Public keys are not human-generated (like usernames) and instead they are random numbers, as such, they do not reveal any information about the owner (think of public keys as pseudonyms). Registration is mandatory for the users who want to publish a message, however, users who only want to listen to the messages are more than welcome and do not have to register in the group.

- Membership fee: Membership is not for free! each peer has to lock a certain amount of funds during the registration (this means peers have to have an Ethereum account with sufficient balance for this sake). This fund is safely stored on the contract and remains intact unless the peer attempts to break the rules and publish more than one message per epoch.

- Zero-knowledge Proof of membership: Do you want your message to get routed to its destination, fine, but you have to prove that you are a member of the group (sorry, no one can escape the registration phase!). Now, you may be thinking that should I attach my public key to my message to prove my membership? Absolutely Not! we said that our solution respects privacy! membership proofs are done in a zero-knowledge manner that is each message will carry cryptographic proof asserting that "the message is generated by one of the current members of the group", so your identity remains private and your anonymity is preserved!

- Slashing through secret sharing: Till now it does not seem like we can catch spammers, right? yes, you are right! now comes the exciting part, detecting spammers and slashing them. The core idea behind the slashing is that each publishing peer (not routing peers!) has to integrate a secret share of its private key inside the message. The secret share is deterministically computed over the private key and the current epoch. The content of this share is harmless for the peer's privacy (it looks random) unless the peer attempts to publish more than one message in the same epoch hence disclosing more than one secret share of its private key. Indeed two distinct shares of the private key under the same epoch are enough to reconstruct the entire private key. Then what should you do with the recovered private key? hurry up! go to the contract and withdraw the private key and claim its fund and get rich!! Are you thinking what if spammers attach junk values instead of valid secret shares? Of course, that wouldn't be cool! so, there is a zero-knowledge proof for this sake as well where the publishing peer has to prove that the secret shares are generated correctly.

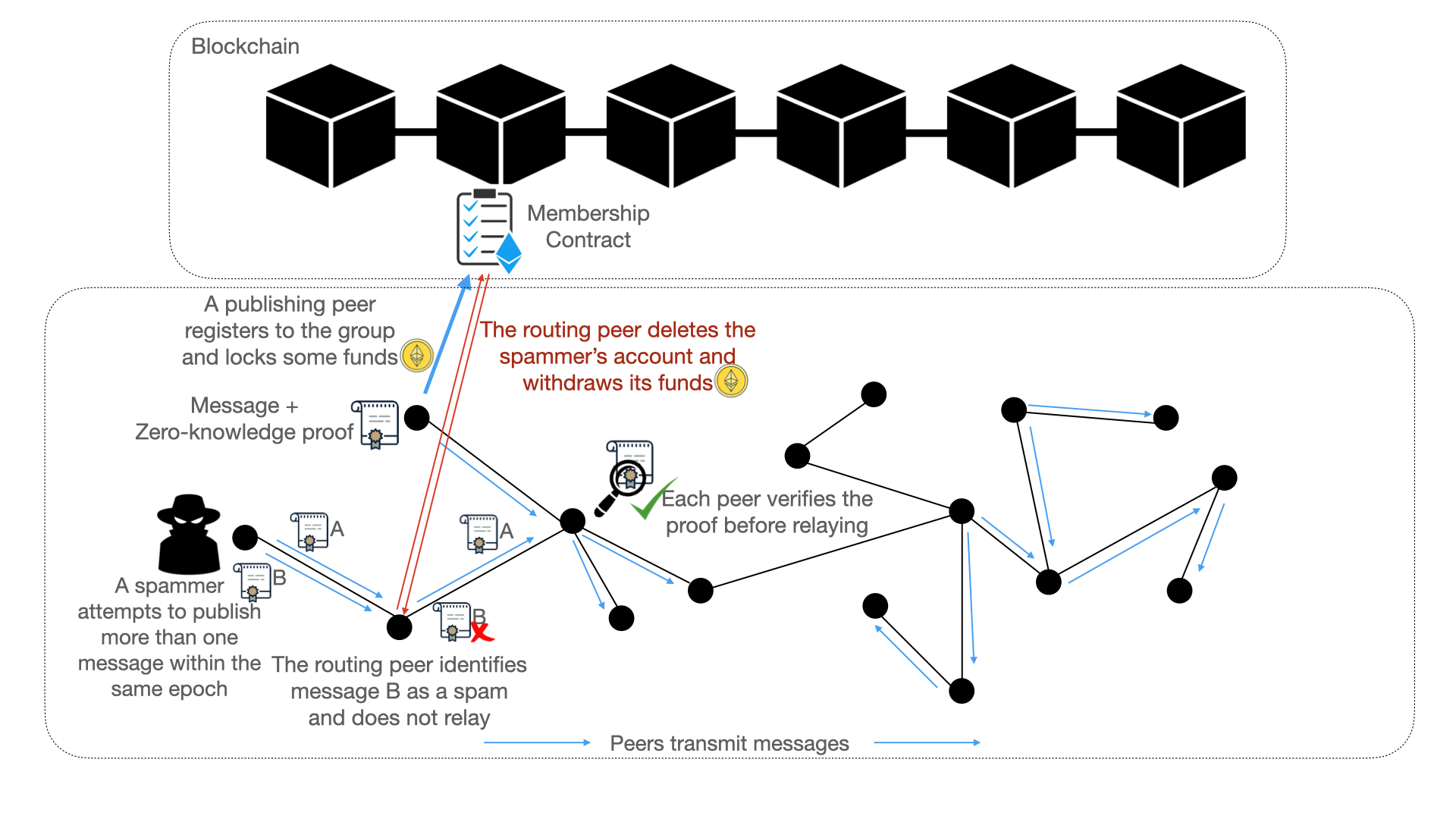

A high-level overview of the economic spam protection is shown in Figure 1.

Flow

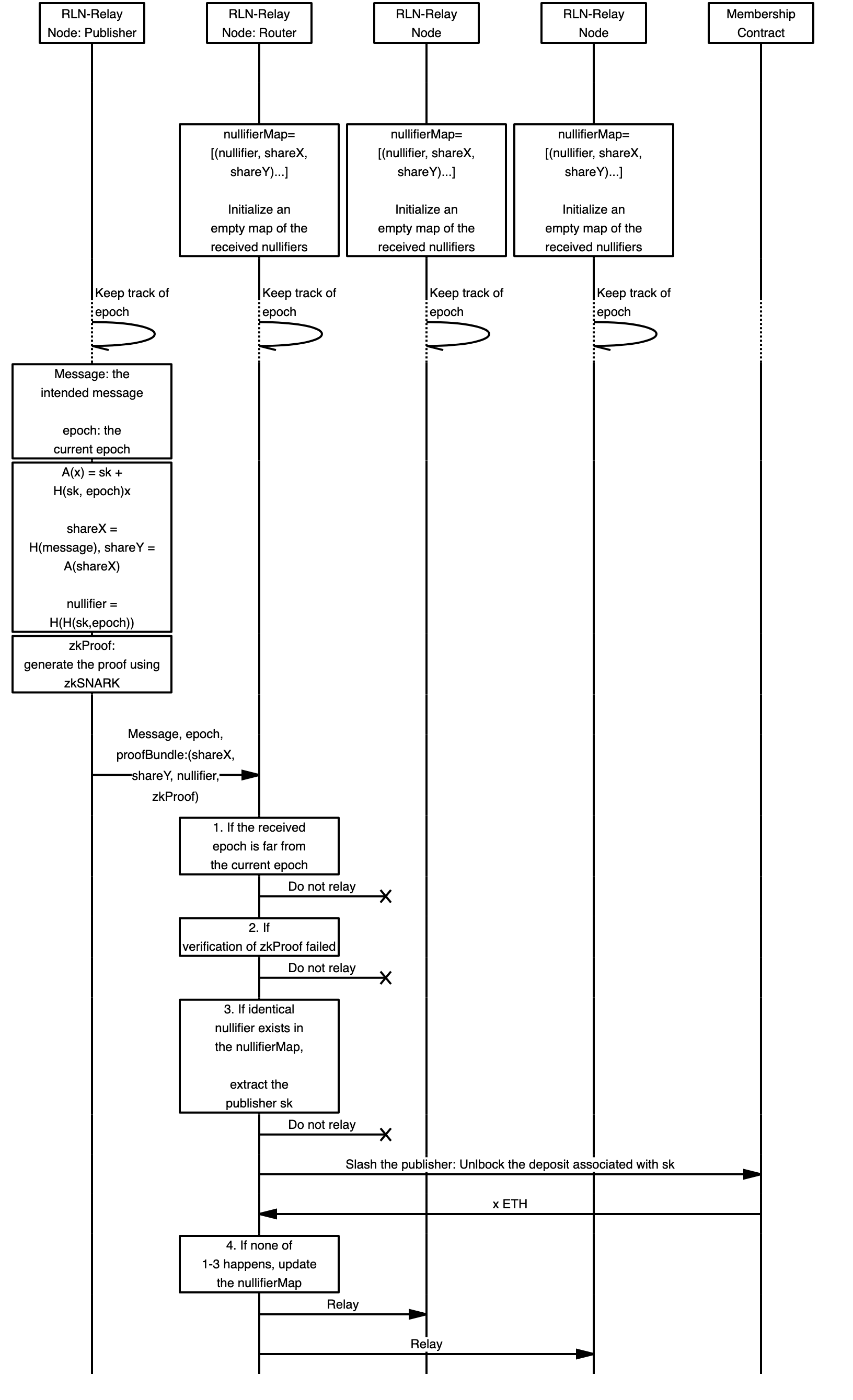

In this section, we describe the flow of the economic-incentive spam detection mechanism from the viewpoint of a single peer. An overview of this flow is provided in Figure 3.

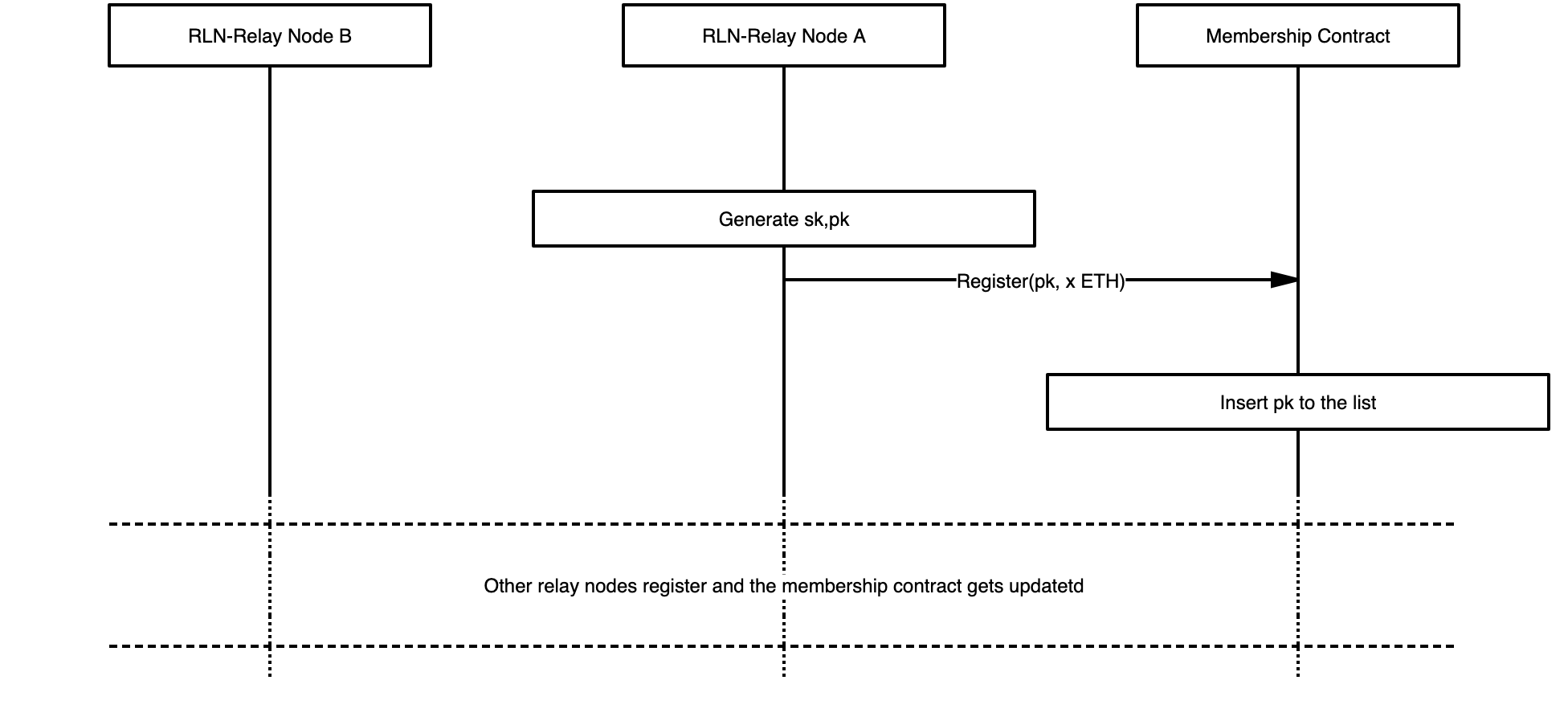

Setup and Registration

A peer willing to publish a message is required to register. Registration is moderated through a smart contract deployed on the Ethereum blockchain. The state of the contract contains the list of registered members' public keys. An overview of registration is illustrated in Figure 2.

For the registration, a peer creates a transaction that sends x amount of Ether to the contract. The peer who has the "private key" sk associated with that deposit would be able to withdraw x Ether by providing valid proof. Note that sk is initially only known by the owning peer however it may get exposed to other peers in case the owner attempts spamming the system i.e., sending more than one message per epoch.

The following relation holds between the sk and pk i.e., pk = H(sk) where H denotes a hash function.

Maintaining the membership Merkle Tree

The ZKP of membership that we mentioned before relies on the representation of the entire group as a Merkle Tree. The tree construction and maintenance is delegated to the peers (the initial idea was to keep the tree on the chain as part of the contract, however, the cost associated with member deletion and insertion was high and unreasonable, please see Feasibility and Open Issues for more details). As such, each peer needs to build the tree locally and sync itself with the contract updates (peer insertion and deletion) to mirror them on its tree. Two pieces of information of the tree are important as they enable peers to generate zero-knowledge proofs. One is the root of the tree and the other is the membership proof (or the authentication path). The tree root is public information whereas the membership proof is private data (or more precisely the index of the peer in the tree).

Publishing

In order to publish at a given epoch, each message must carry a proof i.e., a zero-knowledge proof signifying that the publishing peer is a registered member, and has not exceeded the messaging rate at the given epoch.

Recall that the enforcement of the messaging rate was through associating a secret shared version of the peer's sk into the message together with a ZKP that the secret shares are constructed correctly. As for the secret sharing part, the peer generates the following data:

shareXshareYnullifier

The pair (shareX, shareY) is the secret shared version of sk that are generated using Shamir secret sharing scheme. Having two such pairs for an identical nullifier results in full disclosure of peer's sk and hence burning the associated deposit. Note that the nullifier is a deterministic value derived from sk and epoch therefore any two messages issued by the same peer (i.e., using the same sk) for the same epoch are guaranteed to have identical nullifiers.

Finally, the peer generates a zero-knowledge proof zkProof asserting the membership of the peer in the group and the correctness of the attached secret share (shareX, shareY) and the nullifier. In order to generate a valid proof, the peer needs to have two private inputs i.e., its sk and its authentication path. Other inputs are the tree root, epoch, and the content of the message.

Privacy Hint: Note that the authentication path of each peer depends on the recent list of members (hence changes when new peers register or leave). As such, it is recommended (and necessary for privacy/anonymity) that the publisher updates her authentication path based on the latest status of the group and attempts the proof using the updated version.

An overview of the publishing procedure is provided in Figure 3.

Routing

Upon the receipt of a message, the routing peer needs to decide whether to route it or not. This decision relies on the following factors:

- If the epoch value attached to the message has a non-reasonable gap with the routing peer's current epoch then the message must be dropped (this is to prevent a newly registered peer spamming the system by messaging for all the past epochs).

- The message MUST contain valid proof that gets verified by the routing peer. If the preceding checks are passed successfully, then the message is relayed. In case of an invalid proof, the message is dropped. If spamming is detected, the publishing peer gets slashed (see Spam Detection and Slashing).

An overview of the routing procedure is provided in Figure 3.

Spam Detection and Slashing

In order to enable local spam detection and slashing, routing peers MUST record the nullifier, shareX, and shareY of any incoming message conditioned that it is not spam and has valid proof. To do so, the peer should follow the following steps.

- The routing peer first verifies the

zkProofand drops the message if not verified. - Otherwise, it checks whether a message with an identical

nullifierhas already been relayed.- a) If such message exists and its

shareXandshareYcomponents are different from the incoming message, then slashing takes place (if theshareXandshareYfields of the previously relayed message is identical to the incoming message, then the message is a duplicate and shall be dropped). - b) If none found, then the message gets relayed.

- a) If such message exists and its

An overview of the slashing procedure is provided in Figure 3.

Feasibility and Open Issues

We've come a long way since a year ago, blockers resolved, now we have implemented it end-to-end. We learned lot and could identify further issues and unknowns some of which are blocking getting to production. The summary of the identified issues are presented below.

Storage overhead per peer

Currently, peers are supposed to maintain the entire tree locally and it imposes storage overhead which is linear in the size of the group (see this issue18 for more details). One way to cope with this is to use the light-node and full-node paradigm in which only a subset of peers who are more resourceful retain the tree whereas the light nodes obtain the necessary information by interacting with the full nodes. Another way to approach this problem is through a more storage efficient method (as described in this research issue19) where peers store a partial view of the tree instead of the entire tree. Keeping the partial view lowers the storage complexity to O(log(N)) where N is the size of the group. There are still unknown unknowns to this solution, as such, it must be studied further to become fully functional.

Cost-effective way of member insertion and deletion

Currently, the cost associated with RLN-Relay membership is around 30 USD20. We aim at finding a more cost-effective approach. Please feel free to share with us your solution ideas in this regard in this issue.

Exceeding the messaging rate via multiple registrations

While the economic-incentive solution has an economic incentive to discourage spamming, we should note that there is still expensive attack(s)21 that a spammer can launch to break the messaging rate limit. That is, the attacker can pay for multiple legit registrations e.g., k, hence being able to publish k messages per epoch. We believe that the higher the membership fee is, the less probable would be such an attack, hence a stronger level of spam-protection can be achieved. Following this argument, the high fee associated with the membership (which we listed above as an open problem) can indeed be contributing to a better protection level.

Conclusion and Future Steps

As discussed in this post, Waku RLN Relay can achieve a privacy-preserving economic spam protection through rate-limiting nullifiers. The idea is to financially discourage peers from publishing more than one message per epoch. In specific, exceeding the messaging rate results in a financial charge. Those who violate this rule are called spammers and their messages are spam. The identification of spammers does not rely on any central entity. Also, the financial punishment of spammers is cryptographically guaranteed. In this solution, privacy is guaranteed since: 1) Peers do not have to disclose any piece of personally identifiable information in any phase i.e., neither in the registration nor in the messaging phase 2) Peers can prove that they have not exceeded the messaging rate in a zero-knowledge manner and without leaving any trace to their membership accounts. Furthermore, all the computations are light hence this solution fits the heterogenous p2p messaging system. Note that the zero-knowledge proof parts are handled through zkSNARKs and the benchmarking result can be found in the RLN benchmark report22.

Future steps:

We are still at the PoC level, and the development is in progress. As our future steps,

- we would like to evaluate the running time associated with the Merkle tree operations. Indeed, the need to locally store Merkle tree on each peer was one of the unknowns discovered during this PoC and yet the concrete benchmarking result in this regard is not available.

- We would also like to pursue our storage-efficient Merkle Tree maintenance solution in order to lower the storage overhead of peers.

- In line with the storage optimization, the full-node light-node structure is another path to follow.

- Another possible improvement is to replace the membership contract with a distributed group management scheme e.g., through distributed hash tables. This is to address possible performance issues that the interaction with the Ethereum blockchain may cause. For example, the registration transactions are subject to delay as they have to be mined before being visible in the state of the membership contract. This means peers have to wait for some time before being able to publish any message.

Acknowledgement

Thanks to Onur Kılıç for his explanation and pointers and for assisting with development and runtime issues. Also thanks to Barry Whitehat for his time and insightful comments. Special thanks to Oskar Thoren for his constructive comments and his guides during the development of this PoC and the writeup of this post.

References

Footnotes

-

RLN-Relay specification: https://rfc.vac.dev/waku/standards/core/17/rln-relay ↩

-

RLN documentation: https://hackmd.io/tMTLMYmTR5eynw2lwK9n1w?both ↩

-

RLN repositories: https://github.com/kilic/RLN and https://github.com/kilic/rlnapp ↩ ↩2

-

GossipSub: https://docs.libp2p.io/concepts/publish-subscribe/ ↩

-

Waku Relay: https://rfc.vac.dev/waku/standards/core/11/relay ↩

-

Proof of work: http://www.infosecon.net/workshop/downloads/2004/pdf/clayton.pdf and https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/3-540-48071-4_10.pdf ↩ ↩2

-

EIP-627 Whisper: https://eips.ethereum.org/EIPS/eip-627 ↩

-

Peer Scoring: https://github.com/libp2p/specs/blob/master/pubsub/gossipsub/gossipsub-v1.1.md#peer-scoring ↩ ↩2

-

Peer scoring security issues: https://github.com/vacp2p/research/issues/44 ↩

-

Zero Knowledge Proof: https://dl.acm.org/doi/abs/10.1145/3335741.3335750 and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zero-knowledge_proof ↩

-

zkSNARKs: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-662-49896-5_11 and https://coinpare.io/whitepaper/zcash.pdf ↩

-

Shamir Secret Sharing Scheme: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shamir%27s_Secret_Sharing ↩

-

zkSNARKs proof time: https://github.com/vacp2p/research/issues/7 ↩

-

Prover key size: https://github.com/vacp2p/research/issues/8 ↩

-

The lack of Shamir secret sharing in zkSNARKs: https://github.com/vacp2p/research/issues/10 ↩

-

The MPC required for zkSNARKs trusted setup: https://github.com/vacp2p/research/issues/9 ↩

-

Storage overhead per peer: https://github.com/vacp2p/research/issues/57 ↩

-

Storage-efficient Merkle Tree maintenance: https://github.com/vacp2p/research/pull/54 ↩

-

Cost-effective way of member insertion and deletion: https://github.com/vacp2p/research/issues/56 ↩

-

Attack on the messaging rate: https://github.com/vacp2p/specs/issues/251 ↩

-

RLN Benchmark: https://hackmd.io/tMTLMYmTR5eynw2lwK9n1w?view#Benchmarks ↩