Vac 101: Climbing Merkle Trees

In this post, we introduce a crucial data structure used throughout web3.

Introduction

A large amount of data is swapped between users on a blockchain in the form of transactions. Over the entire life of a blockchain, the storage space required to maintain a copy of every transaction becomes untenable for most users. However, the integrity of a blockchain relies on a large pool of users that can validate the blockchain's history from its inception to its present state. The data representing the blockchain's state is compressed. This compression addresses the issue of scalability that would otherwise greatly restrict the pool of users.

Data compression alone is not the end goal. As mentioned, it is essential for users to be able to validate the blockchain's history. The property of compression and validation was solved in Bitcoin by the use of Merkle trees. Merkle trees were introduced first by Ralph Merkle in his dissertation [1]. A Merkle tree is a data structure that compresses a digest of data to a constant size while still providing a method for proving membership of elements of the digest. A previous rlog[2] described how Merkle trees with their proof of membership could be used for lightweight clients for RLN.

Tree structure

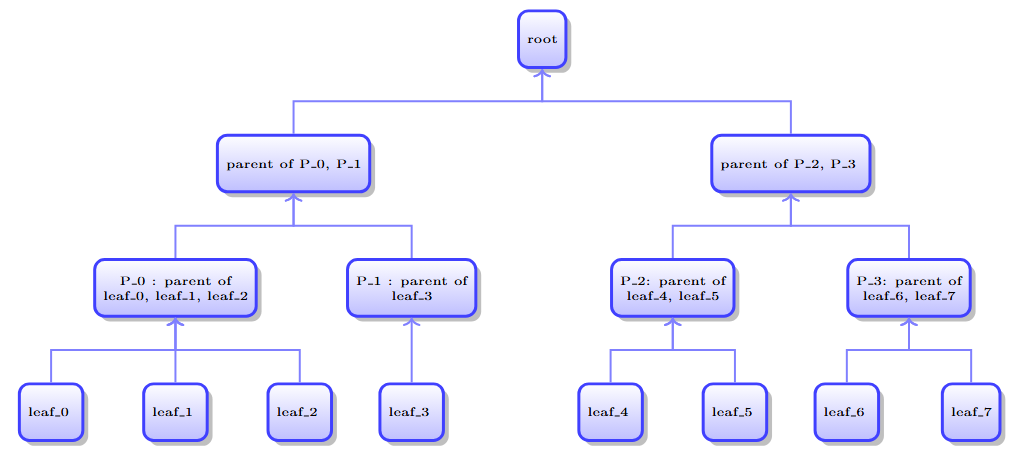

A tree is a special data structure that organizes nodes so that there is exactly one path between any two nodes. The trees that we consider can be arranged in layers with multiple nodes (children) merged into a single node (parent) in the preceding layer. A single node exists in the base layer; this special node is called the root node. The highest level of the tree consists of childless nodes called leaves.

A binary tree has one additional property: each nonleaf node has exactly two children nodes. That is, we assume that nodes in a binary tree are either a parent node with two children or a leaf. As strange as it sounds, each child node has exactly one parental node.

A binary tree with leaves consists of layers. Additionally, such a tree has nodes.

Merkle trees

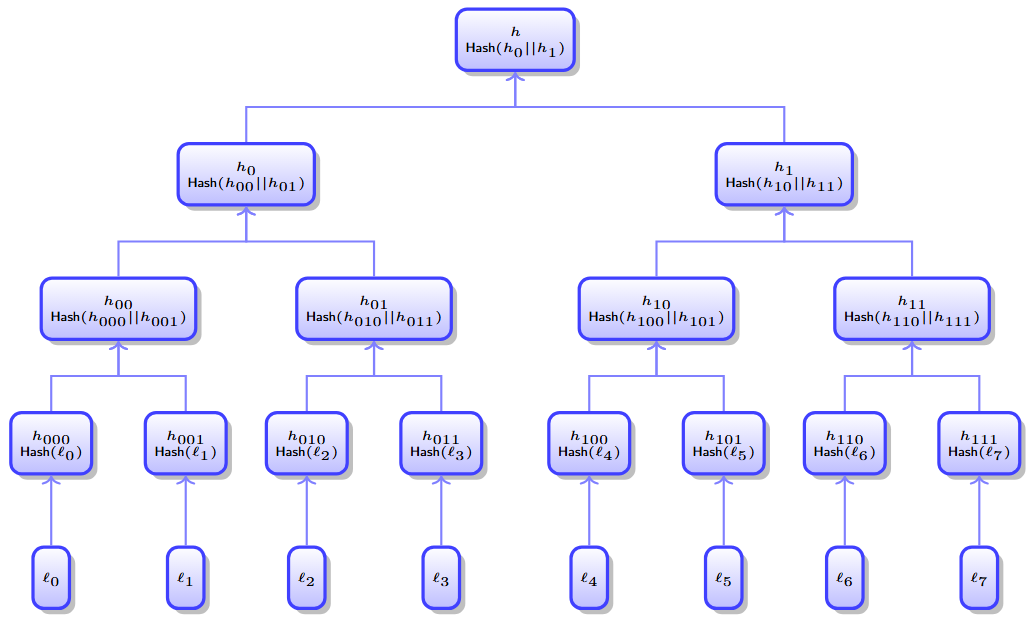

A Merkle tree is a specialized tree in which each node contains the evaluation of a hash function. Merkle trees are usually taken to have a binary tree structure. As such, the presentation we provide in this section will be for binary trees.

Construction

In this section, we show how Merkle trees are constructed to compress a digest . Suppose that the digest consists of entries; we assume that the digest has this many entries since a Merkle tree is a binary tree. Additionally, each digest can be padded to ensure that has the desired number of entries.

Each leaf of the Merkle tree contains the hash of a digest entry. Each parent node contains the hash of the concatenation of their child nodes. Through this iterative construction, we reach the root of the tree. The value contained in the root node is called the root hash. The root hash is a compressed representation of the digest .

Each node in the Merkle tree is computed by taking a hash. Since a binary tree with leaves has nodes, then we need to evaluate hashes to construct the Merkle tree.

Merkle tree intregrity

A large quantity of data can be compressed to a single hash value. A natural question to ask is: could a clever party find another digest that yields a Merkle tree with the same root hash? If possible, this would compromise the ledger since the blockchain's history could be altered. Fortunately, Merkle trees are quite secure. In fact, Merkle trees can be used to both bind and hide a digest.

The Merkle tree is able to bind a digest with one of the properties of hash functions (see our previous Vac 101 [3] for information on hash functions). A hash function is collision resistant; it is infeasible for a malicious party to find two values share the same hash value.

This collision resistance property, essentially, fixes the input to each leaf and into their parent, their parent's parent, and so on.

In certain applications, it may be desirable for the digest of a Merkle tree to be kept confidential. This is achieved with the preimage resistant property of hash functions. A hash function is preimage resistant provided that it is difficult to reverse the hashing operation. It would be necessary for a malicious party to find preimages to each node starting from the root node to determine the original digest.

Now, we see that Merkle trees are secured structures that are tamper resistant.

Proof of membership

An interesting and critical property of Merkle trees is their ability to prove that any piece of data is part of its digest. This can be done with logarithmic storage and logarithmic computation time.

Suppose that we want to show that data is part of the Merkle tree's digest. Additionally, suppose that is the hash function used to construct the tree. We assume that the hash function can be computed in constant-time for any input.

Suppose that a prover provides data to a verifier, and tells the verifier that corresponds to the th leaf of the Merkle tree. For the verifier to be convinced that is part of the digest, he needs to be able to construct the tree's root hash using , , and some additional information from the prover. Specifically, the prover must provide the sibling hashes for each value that the verifier can compute. This enables the verifier to compute the parents of the siblings that the prover provides and the values that he was able to produce himself. The last of the computed parents is the root.

The leaf index indicates whether a hash value provided by the prover is a left or right sibling. This is done by looking at the binary expansion of .

The verifier can compute the leaf . Next, using 's sibling, , provided by the prover, the verifier can compute or depending on whether is a left or right sibling. This pathing continues until the verifier either successfully computes the root hash (in hashes) or fails to do so.

The prover has to provide sibling nodes for the proof of membership.

There is a key detail that is essential for the proof of membership to be secure. The root hash has to be provided to the verifier prior to the selection of data . Otherwise, the prover could generate a series of hash values (with the corresponding root hash) to forge a proof of membership.

Capped proof of membership

Polygon provides an implementation [4] of a shortened proof of membership with a slight modification. A specific layer of the Merkle tree is published instead of just the root hash. By doing this, a capped proof of membership is just the path from leaf to the published layer.

Extensions of Merkle trees

Merkle trees can be extended in multiple ways. In this section, we explore a select few of these extensions.

Sparse Merkle trees

A sparse Merkle tree (SMT) is a special Merkle tree that can be used to represent digests with nonconsecutive entries. Specifically, each digest entry has a particular leaf index. For simplicity, we assume that the index value is computed by taking the hash of the entry. We note that this is a sorted SMT.

Let denote the number of bits that a hash value can possess. This means that our SMT can have at most leaves.

An SMT is treated as a Merkle tree in which each entry is placed in the leaf corresponding to its hash value, and the other entries have a marker inserted in. This means that we can prove membership in the way described. However, we can also prove nonmembership of an element by showing that is located in the element's hash location. The crucial difference between a sorted and unsorted SMT is that the unsorted variant cannot be used to prove nonmembership.

We can take advantage of the sparse nature of SMTs to provide shortened proofs. Specifically, it is unlikely for entries to cluster together. Thus, it is efficient to maintain a list of values:

| Null values |

|---|

Each of the 's represents the root hash of a Merkle tree with leaves containing . These values can be used to shorten the time needed to construct an SMT and the length of proofs.

Proof of nonmembership

In the first Vac 101 [5], we examined Bloom and Cuckoo filters that could be used for proof of membership and nonmembership. However, the proof of membership may result in false positives due to collisions. This would affect nonmembership proofs as well. Sparse Merkle trees can be adapted to provide greater assurance that a given piece of data is not a member of the digest.

Why is sorting essential? The sorting mechanism of data can be arbitrarily chosen. However, it is essential that there are no gaps in the ordering. The maximum number of elements that could ever exist in the digest must be known. A simple method for this is to use a hash function to provide fingerprints to the data. Each hash using either SHA-256 or Keccak has 256-bits. Our entire digest could consist of a maximum of entries. This assumes that our digest does not contain collisions.

The fingerprint of a piece of data indicates which leaf of the SMT it is contained in. This means that a nonmembership of in the SMT becomes a matter of proving that is contained in 's location.

It is crucial for the SMT to be sorted. Otherwise, a malicious party can append the entry to a random location. This allows for the malicious party to provide contradictory proofs that prove both membership and nonmembership. We note that the requirement that an SMT is sorted may be too strong of an assumption in centralized cases. However, sortedness is a necessary property of SMTs for decentralized systems.

Verkle Trees

A proof of membership grows in length as the Merkle tree grows. The most obvious approach to remedy this scalability issue is to use Merkle trees in which each node has more than two children. However, this does not fix the issue. A proof of membership in a -nary Merkle tree [6] (each node has children) has a proof size . The multiple is the number of silbings that a node has on each layer. Hence, the proof size grows faster than a logarithmic function of the digest size.

An alternate approach is to use a different data structure: Verkle trees [6]. A Verkle tree replaces hash functions with polynomial commitments [7, 8]. We will explore Verkle trees in a future Vac 101 edition.